The Anolis ecomorphs are an interesting case of evolution. Several different but morphologically similar species are found on different islands in the Caribbean. So big questions arise from this panorama: did the species evolve once and then end up on the islands somehow? Or did the species evolve independently on each of the islands? That’s what we’re going to explore in this article.

Similar species coexist by occupying different ecological niches, which we’ll get to later. The occupation of these niches results in an evolution associated with morphologies. Aquatic species having fins and cave species using senses other than sight are strong indications for this theory of morphology. It was because of this correlation that the concept of Greater Antillean Anolis lizards came about. Due to such a characteristic evolution in these lizards, this concept has been applied to more species of spiders, finches and cichlids.

Environment

It is thought that the environment on the mainland is much more complex than on islands, with a greater number of predators, more competitors and a greater diversity of habitats. These factors can compensate for morphological divergences in relative species, but when it comes to islands, adaptive radiation is encouraged. This is because species can live more freely, as there are more niches to be occupied without predators. Competition can be fierce for individuals of the same species, but we’ll get to that later in this article. This is called adaptive radiation, where many species arise from a common ancestor quickly when ecological niches emerge1.

The different size of the lizards also has a function, the size of the head is correlated with feeding habits. The length of the limbs is related to the niche, larger legs would be useful for jumping into Anolis close to the ground, for example. And the size of the body has a clear correlation with all its characteristics, offering protection.

Ecomorphs: Caribbean species

In the Caribbean there are more than 150 species of anole lizards. First, we will explore the habitat and make observations of these lizards. 4 from Puerto Rico and 4 from the nearby island of Hispaniola.

The anolis on the island of Puerto Rico feed on similar things. Such as crickets and smaller spiders. The ones with longer tails live in grasses and bushes. On the ground and under the trunks of trees, we have one with long legs. On branches and twigs at medium height, we have anolis with very short legs. Up in the tree you’ll find a much larger anolis with big legs, it’s also green. Each species lives in a different vertical environment on that island, which gives them a different opportunity. They all share the ecosystem, as they specialize in a specific area of the land. By not competing directly against each other, this will reduce competition, which in the long run will result in species that occupy different niches in the same ecosystem.

If they lived and competed against each other, they would eliminate each other, and only the strongest would come out on top. In this way, more species can coexist, as their niches never overlap.

The Ecomorphs

Among the ecomorphs are:

Bush anolis with long tails, this one lives in bushes or grass. Long leg trunk-ground Anolis, this one lives in the trunk region of trees close to the ground. Short legged twig anolis, a little higher up, this one lives in the branches of trees. And canopy anolis with large toe pads, this one lives in the crown of trees.

Ecomorphs literally means, “species with the same structural habitat or niche, similar in morphology and behavior, but not necessarily close phyletically“.2 So, this means that this anoles ecomorphs are not the same species, but different species morphologically close and habitat wise.

On each of the islands we can see individuals with the same morphological characteristics. What I mean is that you can find Long leg trunk-ground Anolis on all the islands, and they share the same morphology, for example.

Ecomorphs Phylogeny

The big question that remains is. Did this characteristic appear just once and then spread to each of the islands? Or did it evolve several times and on each of the islands? This could be an interesting case for understanding how evolution works. Luckily, genetics can help us solve this huge question.

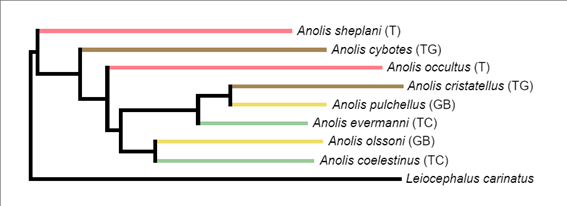

Fig. 1- Anolis phylogeny on both islands. T- Twig Anolis. TG- Represents Trunk-Ground Anolis. GB- Grass-Bush Anolis. TC- Trunk Crown Anolis

Here we have the phylogeny of some anolis species from two different islands. As we can see, the same ecomorphs are not so genetically close to each other, and are even closer to other species from different habitats.

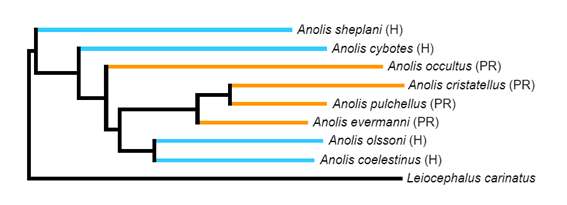

Fig. 2- Anolis phylogeny in different islands. H- Hispaniola Island PR- Puerto Rico

As we can see from this phylogenetic tree, in general, species are closer to each other when they are from the same island. This evidence brings us closer to the answer, stating that, most probably, these characteristics arose independently on each of the islands. Although the morphological characteristics are very similar between islands, like A. occultus and A. sheplani, they are not so close genetically, being closer to other anolis that live on the same island.

This is a huge example of convergent evolution, where similar traits have emerged due to similar selective pressures, in unrelated individuals.

Experiment

They put lizards on 7 islands that didn’t have anolis near Iron Cay in the Bahamas, but they also put them on Iron Cay. On Iron Cay, they put them in an area where there were large trees. Whereas on the experimental islands, there were only small grasses and bushes. Then they analyzed the data obtained over 4 years.3

After several generations, 10 anoles were measured from each island and Iron Cay. On average, those from Iron Cay had longer legs than those from the experimental islands.

O Anolis sagrei,the species used in this experiment, is a trunk anolis.

To try to explain this situation, evolution may come into question. Perhaps there is some kind of selection for short legs on the experimental islands and for longer legs in the individuals on Iron Cay. But these conclusions are to be taken with added salt, we can’t conclude anything just based on 10 X-rays of different anolis.

Dewlaps And Reproduction

For one species to be considered different from another, there must be no reproduction, this is called isolated reproduction. To attract females, Anolis use Dewlaps. The most interesting thing is that each of these species has a slightly different Dewlap, which may be the key to the difference that causes isolated reproduction.

For species that live in darker environmental niches, a lighter dewlap can be very effective in attracting females from a great distance. The opposite is also true: if an environment has more sunlight, a darker dewlap can help to overlap the light emitted by our star, attracting females of its species.

One of the ways in which a species can become different when they descend from a common species is related to geographical isolation. A population of individuals becomes geographically isolated and spends several generations in that location. After many generations, even if their habitats overlapped again, they would no longer be able to reproduce.

It’s worth noting that natural effects can cause these barriers that separate populations of a species. And the length of time they are separated is also another crucial factor; a short separation time would not be enough for different species to form.

If there were a difference in the color of the dewlaps, due to environmental light, even if the initial populations were to come back into contact, the females of one species would probably not recognize the males of the other species, making both populations reproductively isolated. Over time, these new species will have a strong tendency to live in different niches. In this way, competition is much less or even non-existent, which allows both species to coexist. In the case of overlapping niches, competition would be fierce and would probably eliminate one of the species, the least fit.

Footnotes

- Poe, S., & Anderson, C. G. (2019). The existence and evolution of morphotypes in Anolis lizards: coexistence patterns, not adaptive radiations, distinguish mainland and island faunas. PeerJ, 6, e6040. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6040) ↩︎

- Williams, Ernest E. (1972). “3. The Origin of Faunas. Evolution of Lizard. Congeners in a Complex. Island Fauna: A Trial Analysis”. In T. Dobzhansky; et al. (eds.). Evolutionary Biology. Meredith Corporation. pp. 47–89. ↩︎

- Some information was taken from Lizard Evolution Virtual Lab: HHMI’s BioInteractive ↩︎

Thank you for reading. If you’re curious and want to learn more, go to the “articles” section. Every week there are new articles published and new curiosities, stay tuned! Subscribing to our Newsletter will notify you when a new article drops.

Read Next